Freshwater scarcity is rapidly becoming one of the defining challenges of the 21st century. As droughts intensify and traditional water sources come under pressure, cities around the world are experiencing unprecedented water stress. Many of these cities sit in coastal regions—ironically surrounded by moist air that remains largely untapped.

At the same time, climate change is reshaping the global water cycle. Rising temperatures are drying out rivers and lakes, while increasing the total amount of water held in the atmosphere. In fact, the atmosphere is Earth’s largest single reservoir of freshwater. The challenge is no longer whether water exists—but how efficiently we can access it.

That challenge has given rise to a new wave of innovation in atmospheric water generators (AWGs), and the field is now approaching a critical inflection point.

The Limits of Traditional Atmospheric Water Harvesting

Until recently, commercial atmospheric water harvesting relied on two main approaches:

- Vapour compression, essentially a refrigeration cycle that cools air until moisture condenses

- Desiccant dehumidification, which uses hygroscopic materials to absorb water from air

Both methods work, but neither scales efficiently. Refrigeration systems consume large amounts of electricity, particularly in dry climates, while traditional desiccants require substantial energy to release the captured water. These limitations have kept AWGs niche rather than mainstream.

That equation is now changing—thanks to an entirely new class of materials.

Metal Organic Frameworks: A New Materials Breakthrough

The breakthrough comes from Metal Organic Frameworks, or MOFs—engineered crystalline materials with internal surface areas unlike anything found in conventional solids.

The scientific foundations of MOFs were pioneered by Omar Yaghi, whose work is widely regarded as Nobel-calibre for its impact on materials science. Unlike traditional materials, MOFs are designed at the molecular level, allowing researchers to precisely control how they interact with gases and vapours.

One of their most remarkable properties is their ability to capture water molecules directly from air—even in extremely dry environments. In laboratory and field experiments, MOFs have demonstrated the ability to extract usable quantities of water from desert air, enough not only to sustain human life but even to support plant growth.

Just as important is how efficiently MOFs release that water.

Breaking the Energy Trade-Off

Conventional sorbent materials face a stubborn trade-off: the more water they absorb, the more energy is required to recover it. MOFs break this limitation by combining strong water uptake with exceptionally low regeneration energy.

It’s important to note that MOFs are not a single material, but an entire family of structures. Some variants excel at holding large amounts of moisture, while others are optimized for rapid loading and unloading. Choosing the right MOF is critical—and it’s here that laboratory science has finally crossed into real-world infrastructure.

AirJoule and the First Commercial MOF-Based AWG

After several years of development largely out of public view, AirJoule has successfully commercialized MOF-based atmospheric water harvesting.

To put its performance into perspective:

- Conventional AWGs typically produce 3–3.5 litres of water per kilowatt-hour

- AirJoule’s system delivers approximately 5 litres per kilowatt-hour, setting a new industry benchmark

This improvement isn’t incremental—it represents a fundamental leap in efficiency.

How the System Works

AirJoule’s system operates in three distinct stages:

1. Moisture capture

Ambient air is passed through a mesh—reportedly aluminium fins coated with a MOF—which acts as a highly efficient moisture trap, pulling water molecules directly from the air.

2. Low-energy release under vacuum

Once the MOF is saturated, airflow is sealed off and a controlled vacuum is applied along with a modest amount of heat. Under vacuum conditions, the energy required to release water drops dramatically. The water vapour is distilled out of the sorbent chamber and condensed into liquid water.

3. Flexible energy inputs

Crucially, the heat required does not need to come from electricity. Waste heat or solar thermal energy can be used instead, significantly lowering operating costs.

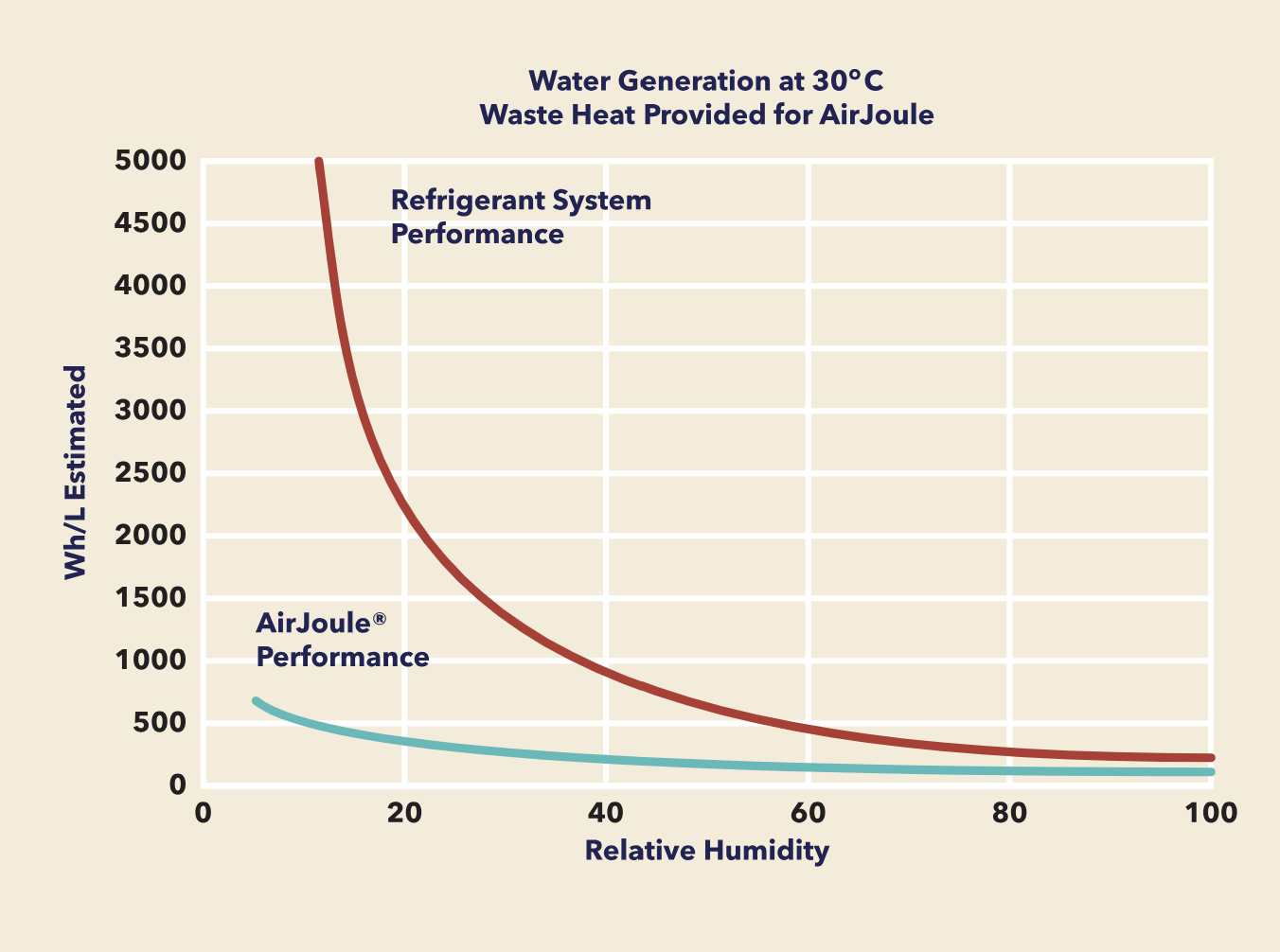

In theory, the system can operate at energy requirements as low as 150 watt-hours per litre. In real-world conditions, this translates to roughly 200 watt-hours per litre—about half the energy consumption of conventional refrigerant-based systems. At low humidity, the efficiency advantage becomes even more dramatic, widening by nearly an order of magnitude.

Industrial Scale and Real-World Impact

AirJoule’s current commercial offering, the A1000, is an industrial-scale unit designed for continuous operation. Under conditions of 30°C and 60% relative humidity, it can produce up to 3,000 litres of water per day. The system occupies roughly the footprint of a shipping container and operates without any refrigerants—a notable environmental advantage.

The implications extend far beyond drinking water. MOF-based atmospheric water systems can be integrated into data centres, reducing cooling loads while simultaneously recovering water. They also offer a compelling solution for remote and arid regions where traditional water infrastructure is impractical or prohibitively expensive.

Rethinking Water, Energy, and Air

This is more than a better water machine. MOF-based atmospheric water harvesting represents a fundamental shift in how we think about water, energy, and the built environment. As the technology matures, it has the potential to reshape not only how we generate drinking water, but how we design the next generation of HVAC, cooling, and energy-efficient infrastructure.

Water has always been around us. For the first time, we’re learning how to collect it efficiently—from thin air.