Have you ever wondered how modern airborne, helium-filled aerostats can do something that seems almost impossible—lifting wind turbines thousands of meters into the sky while also carrying heavy electrical tethers back down to the ground?

Those tethers, packed with electrical conductors that transmit power from the turbine to ground stations, represent one of the greatest engineering challenges in airborne wind energy. Yet recent real-world tests suggest the challenge is being overcome.

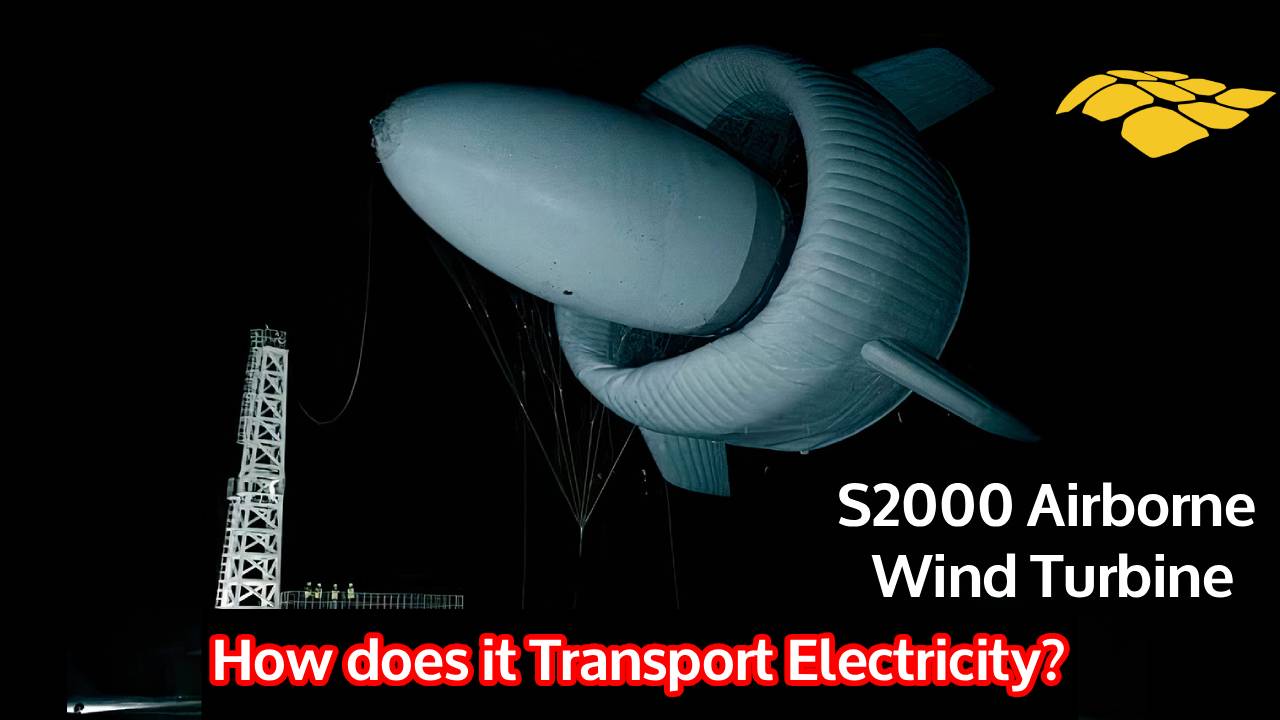

A High-Altitude Milestone

Recently, China tested an advanced airborne wind turbine known as the S2000, which reportedly climbed to an altitude of 3,000 meters and generated 385 kWh of electricity in just 30 minutes.

This achievement immediately raises a critical question: how does such a system generate enough lift to support not only the turbine and onboard electronics, but also a 3-kilometer-long electricity-carrying tether?

To answer that, we need to look at the physics behind lift—both buoyant and aerodynamic.

The Physics of Buoyant Lift

Helium is lighter than air, which makes it ideal for high-altitude aerostats. As a rule of thumb, one cubic meter of helium provides roughly one kilogram of lift.

Now consider the tether itself.

How Heavy Is a 3,000-Meter Tether?

If aluminum is used as the electrical conductor, a 17 mm diameter aluminum cable weighs about 0.6 kg per meter and can carry approximately 133 amps of current.

Once insulation and structural reinforcement are added—typically lightweight, high-strength materials such as Kevlar or Dyneema—the total mass of the tether can be reasonably estimated at around one kilogram per meter.

At an altitude of 3,000 meters, that means the tether alone weighs approximately 3,000 kilograms. To lift just the tether using buoyancy alone, the system would therefore require roughly 3,000 cubic meters of helium.

Can an Aerostat Carry That Much Helium?

At first glance, this sounds demanding, but it is well within reach.An aerostat measuring roughly 60 meters in length, 40 meters in width, and 40 meters in height has a volume far exceeding 3,000 cubic meters. When its specialized geometry is taken into account—often a prolate spheroid core combined with a rim or lifting body section—the total helium capacity can realistically reach between 15,000 and 18,000 cubic meters.

That leaves ample lift capacity for the turbine itself, onboard power electronics, structural components, and operational safety margins.

The High-Altitude Challenge

As airborne wind turbines grow larger and operate at even higher altitudes, a new problem emerges. Air density decreases with altitude, and the buoyant lift provided by helium drops accordingly. Relying on buoyancy alone would eventually limit how high these systems could climb.

The Secret: Hybrid Lift Design

Modern aerostats are not just passive balloons. Their shapes are carefully designed to generate aerodynamic lift, much like an aircraft wing. As wind flows over the aerostat’s streamlined body, it produces additional upward force.

In these systems, buoyant lift from helium supports the static weight, while aerodynamic lift generated by wind enables greater altitude, stability, and load capacity. This hybrid approach allows airborne wind turbines to ascend higher than buoyancy alone would permit, even while supporting long, heavy power tethers.

Why This Matters for the Future of Wind Energy

High-altitude winds are stronger, more consistent, and available across wider geographic regions. By combining helium buoyancy with aerodynamic lift, airborne wind energy systems become not only feasible, but scalable—opening the door to clean energy generation at altitudes once thought impractical.

What once seemed like science fiction—wind turbines floating kilometers above the Earth—is rapidly becoming an engineered reality.

If you’d like, I can also refine this for a technical audience, adapt it for publication on a specific platform, or add diagrams and equations to support the physics.